←BACK

Hówašte Profile : Donald Montileaux

February 16, 2018

|

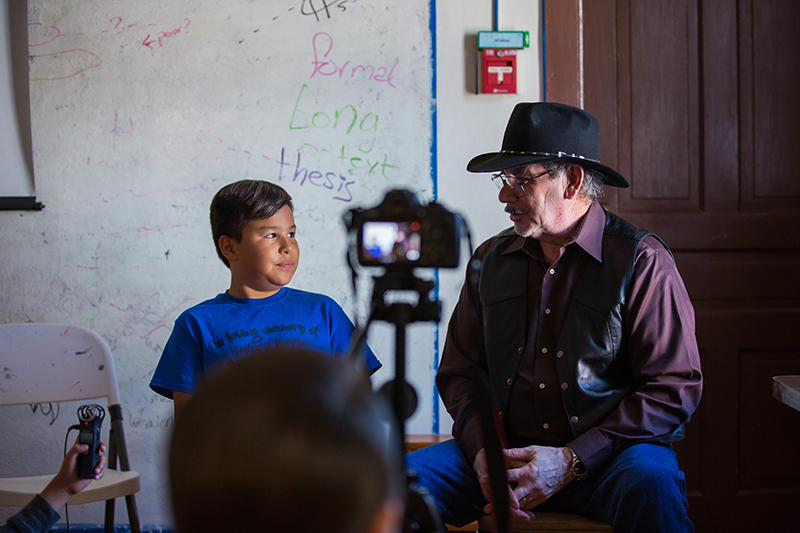

Don participates in "Our Community Story", a student-lead film project.

|

When Donald Montileaux recounts his earliest memory of being an artist, he describes evenings spent drawing with his father after supper.

“When my mother was done washing the dishes she would check on our drawings,” he says, “and we’d have a little art contest. She was prejudiced and would always make me the winner. That was how it was installed in me, to achieve a little bit better each time.”

After moving from Kyle, SD on the Pine Ridge Reservation to Rapid City, SD in the 1950’s, Donald attended a small parochial school that did not offer much in the way of arts education. Once he reached high school, however, Donald took every art class that was available. During that period, he also earned a sponsorship from the Sioux Indian Museum in Rapid City to attend a summer workshop program with Oscar Howe, an internationally admired Native artist and teacher at the University of South Dakota. Donald was so impacted by his interactions with Oscar Howe that they developed an ongoing mentoring relationship.

After high school, Donald’s growing passion for the arts was emboldened when he was recruited to attend the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, NM, a hotbed for the development of contemporary Native artists. Donald’s experience at IAIA opened his eyes to the diversity of Native art, and the different perspectives each tribal culture had to offer.

“We’d all sit down together after supper in the dorm,” he says of his classmates, “and we’d tell stories. You really learn how to respect individuals and their unique artistic visions.”

|

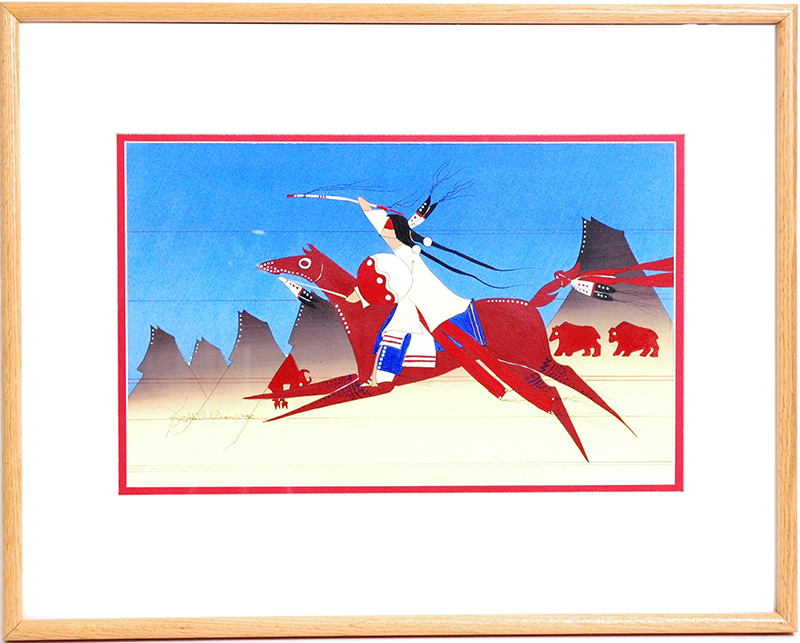

Fast Food, 1994, watercolor, pencil - Courtesy The Heritage Center's permanent collection.

|

Not long after his time at IAIA, Donald sought out a mentoring relationship with fellow Native artist Herman Red Elk, which helped him hone his own artistic style. The elegant, long-legged horses that are a signature of Donald’s work are actually inspired by a story Herman shared with Donald many years ago.

“One day Herman and I were sitting, talking, having a smoke, and he was telling me a story. He said that when the Lakota were attacked, they always looked for a rise in the landscape that they could come off of, and they always had a pouch underneath their horse’s mouth. Inside that pouch were herbs and spices, and it gave the horse a burst of energy,” he said. “When they came off that hill into battle, they jerked that pouch into the horse’s mouth and the horse would ‘fly down the hill’. As soon as Herman said ‘fly down the hill,’my horses never loped or galloped again. My horses fly. That’s why their legs are elongated.”

Not wanting to compete with Herman, who was a renowned buffalo hide painter, Donald gravitated towards using ledger paper for his art. Native art on ledger paper is a tradition derived from a period in the 19th-century when the buffalo population in the plains plummeted due to the encroachment of European settlers and government-paid hunters who slaughtered the buffalo as trophies. With a lack of hides available as canvas for tribal artwork, Native Americans would barter with traders and soldiers for pages of used ledger books in exchange for other goods. At that time, the Lakota still did not have a written language, and so the artwork created on these pages served as a way to preserve history.

“We saved our culture through these old books and these drawings on the pages. They showed that family their history. How their grandfather used to dress on his war horse, how his war horse was painted and designed, what he carried into battle. If he carried a bow or a lance, what society he was in, what he could wear in his hair, what headdress, or feather,” he explained. “That’s what we used to put on hides, and that art carried over into ledger books.”

The ledger art that Donald creates today serves not only as a means of preserving images of traditional Lakota life, but also of educating art lovers and art collectors about the Northern Plains tribal culture. He credits art shows as an important means of spreading awareness about the unique styles of art produced in the Northern Plains, as well as a way for artists to gain access to both financial support and feedback.

“Every time you sell a piece, when you’re younger and just starting out, you’re just blown away,” he said. “As you grow and mature, selling a piece really motivates you to do another one. It really gives you confidence that there’s someone out there that likes your work. Then as you develop, you learn that they might buy my artwork because they like it, but they are also buying me, because I’m the individual who is going to be creating more. And as my reputation grows, so does the work that’s on their walls. It grows in price because of who I am as an artist.”

|

Two Bears, 1996, watercolor, pencil - Courtesy The Heritage Center's permanent collection.

|

The Red Cloud Indian Art Show, which marks its 50th anniversary this year, was the very first show Donald entered as a young artist. And since its start in 1968, he has been a participant each and every year. Although the show had humble beginnings, over five decades it has garnered a reputation not only among local and regional artists, but also on a national scale.

Donald notes that the Red Cloud Indian Art Show is known as a venue where artwork consistently sells, which is a major motivator for artists who are developing their craft and working to catch the eye of collectors.

“The Red Cloud Indian Art Show gives young artists the opportunity to show their work with mature, recognized artists. And audiences who follow those recognized artists also get a chance to see the work of the younger artists—to get a glimpse of what’s coming up,” he said. “Those collectors may end up investing in that young artist, watching them grow and develop, and helping them along, like they did for me.”

Donald’s relationship with The Heritage Center remains strong 50 years later. And indeed, each story Donald Montileaux tells of his journey as an artist is stitched together by his relationships—with family, friends, mentors, mentees, fellow artists, and institutions like IAIA and The Heritage Center. He draws inspiration in that relational aspect of art—and from the many mentors, fellow artists, and relatives—who have shaped his experience and perspective as a creator. And in all his artwork, he celebrates that interconnection.

“I used to dance traditional dance, and when I was [at IAIA] in Santa Fe, a guy wrote a poem about dressing in his costume to dance. He said, ‘When I put on my moccasins, I think of my grandma, because I remember her stitching them with sinew and putting on the rawhide sole. When I look at my leggings, I think of my grandpa and how he sewed those leggings together.In the same way, when I make that first step in the dance, I am no longer who I am now, I am all my relatives, and that’s how we dance, as my relatives,’” he remembered.

“I thought, man—that’s so cool. I could dance ten times longer than I could if I didn’t have all those people’s spirits within me. All those things, that’s who an artist is. He’s not one person, he’s all these individuals.”

|

Photos © Red Cloud Indian School

Want to receive more stories like this?